In 1965, a folk-rock band, ‘The Byrds’, recorded their version of Pete Seeger’s song, ‘Turn, Turn, Turn’. The lyrics refer to there being a time for many activities and events, including a time to plant and a time to harvest. Although I’ve heard the song hundreds of times over the years, it had a new meaning for me when I became a supply chain manager.

Consumers want the freshest food possible, necessitating that manufacturers maintain the freshest inventory possible. This is especially true for fruits and vegetables used in processed or semi-processed foods. If these fruits and vegetables are grown in specific geographies, it can be very difficult to maintain a fresh inventory year round. Under these circumstances, purchasing the correct amount of these items is a challenge, and not having enough material to cover the requirements before the next harvest is an obvious problem. Conversely, purchasing too much material can be a problem if the shelf-life of perishable items expires before they can be utilized.

One of the biggest challenges of my career was managing the inventory of perishable materials. My colleagues and I developed a system for calculating the quantity of material to be purchased based on when new material needed to be contracted/purchased and the forecasted rate of the material’s consumption in the production of finished goods.

We determined that it worked best for the people in charge of procurement to frequently talk directly with operations people who have knowledge of the business and production planning. This not only guaranteed the freshest possible product for our customers, it reduced financial losses due to expired materials. It also minimized the need to make emergency purchases at a higher cost on the spot market to make up for shortfalls in the inventory. To facilitate these discussions, we developed a sophisticated spreadsheet tool to capture pertinent information.

Based on our experience, here are the recommended steps for developing an inventory management tool and using it to plan the best purchasing strategy for your business.

- Establish the parameters for product availability

List all of the items to be purchased and then answer a few simple questions about everything on the list: What is the shelf life of the material? Where is the item grown? Is it available from sources outside of your country? Is it available in the opposite hemisphere, i.e., if you are located in the northern hemisphere, can the item be grown in the southern hemisphere and shipped economically to your location? Once this information is developed, the purchasing plan can be established.

- Develop a consumption model

To predict the consumption of the material, a model will be required to show the projected inventory level of each item. This will require the production forecast by month, and the amount of material used in each finished good item to calculate the usage. Monthly consumption is the most convenient way to view the information. When developing the model, a ‘loss factor’ should be added to the formula to account for material wasted or damaged during storage and/or manufacturing. If the material is used in multiple finished good items, cumulative usage should be tracked and reported as a single number.

- Develop the inventory model

Utilize the product availability parameters (step 1) and consumption model (step 2) to set up a tool that will show the inventory levels at the beginning or end of each month. The third variable in the inventory model should show the contracted quantities and when the material is available for usage.

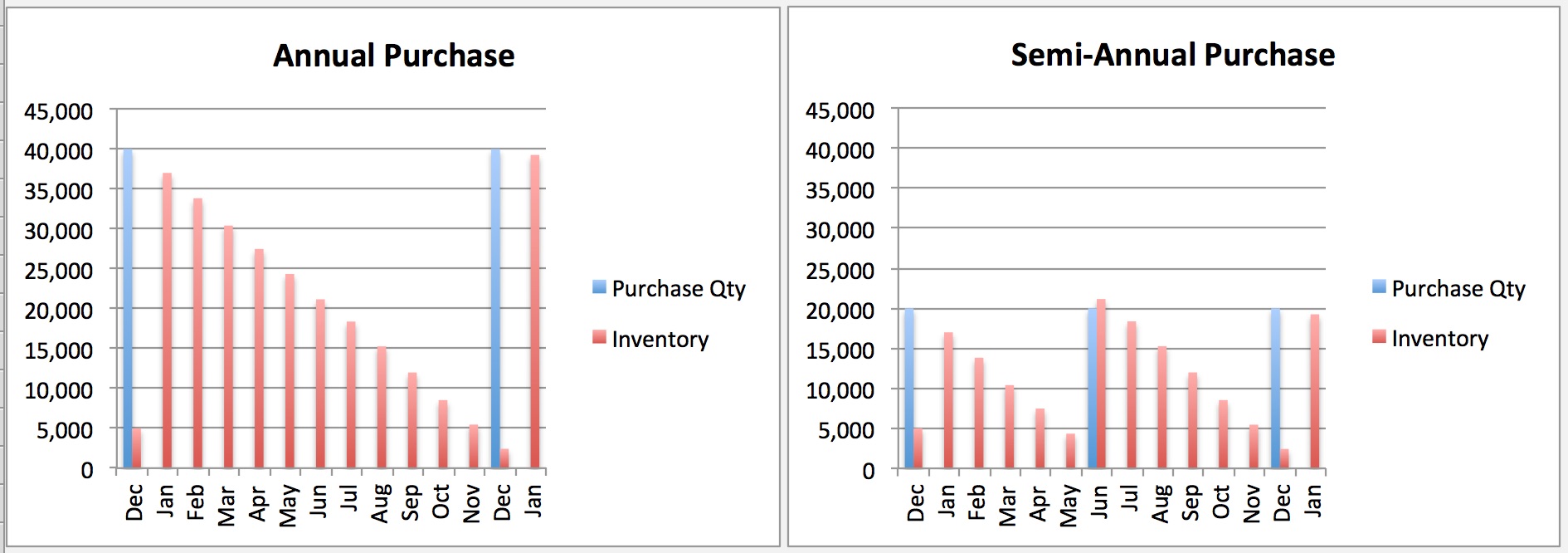

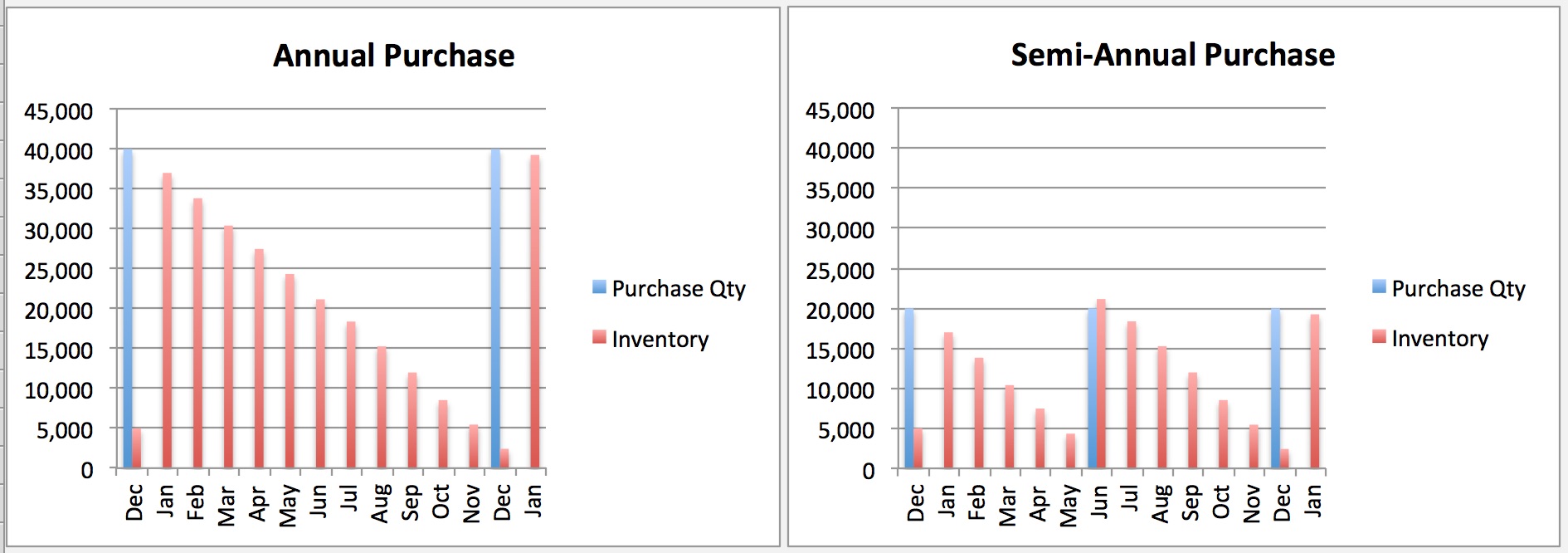

Combining the inventory, consumption, and purchase quantity will generate a ‘strategic’ view of the available inventory over time. Understanding the strategic view of the inventory will indicate when to purchase the material again in the future.

Once the inventory model is working and actual inventories are updated each month, the inventory levels can be predicted for each time period. Management can then determine if there is a risk of running out of materials or conversely, predict if there will be excess material left over that will expire before it can be used. Examples of an annual purchase and semi-annual purchase inventory model are shown below:

- Review Inventory and Adjust Purchasing Strategy

The most important step of this process is for the appropriate parties to review the inventory positions on a monthly basis, even if the purchase date is several months away. For example, if sales are not going as planned, then a strategy can be developed to manage the potential issues of running out of material prematurely or having excess material that will expire and cannot be used. Ideally the Operations group will know how sales are trending and this intelligence can be brought to the attention of the Procurement group.

- Establish Timetables for Making a Purchase Decision

The process works well when a timetable is developed for each item. In general, the process is to jointly review the inventory plan and forecast 3 months prior to when the material is available for purchase. The forecast should be verified with the Production Planning/Scheduling department two months prior to contracting the item. This gives Procurement enough time to develop the quantity requirements and negotiation strategy to be executed in the month prior to the delivery on the contract.

Some companies may have ERP/MRP systems that will generate similar information for a material, however, it is important to have a tool to facilitate the discussions between Procurement and Operations. These discussions need to take place with some frequency to ensure necessary adaptations to business plans.

It may take a few months to develop and launch this entire process, but once it is running and the monthly review of inventory is taking place between Procurement and Operations, the benefits are substantial. Having a sensitive and efficient process for updating the consumption model and the inventory model is key to success. Accurate and timely information will lead to better decisions and improved business results.

It is safe to say that the Byrds were not thinking about inventory position and consumption models when they recorded one of their most famous songs, but it’s easy to hear the wisdom in their chorus:

‘There is a season – turn, turn, turn

And a time to every purpose under heaven’